Augmented Reality and a Creative Commons for Physical Objects

The Augmented Reality Cloud is creating a ‘digital twin’ of the physical world. Physical places are being scanned, anchors are being set, the relationship between objects are being mapped.

But should physical objects and spaces have “rights”? When you can easily overlay digital content on a physical object, does the physical object itself have any agency?

They may seem like esoteric questions, And yet it won’t be long before there’s a clash. Because the ‘owners’ of physical spaces and objects will start to come in conflict with the value created by adding a digital overlay.

We need a Creative Commons for physical objects.

Imagining Our Augmented Future

Augmented reality allows us to add digital content to our views of physical reality. Currently, those views are created by rough ‘scans’ of the world around us by, say, the camera on our phone.

AI is used to further identify objects. Anytime you use a Snapchat filter, AI is powering the recognition and mapping of your face so that an AR effect can be added to your selfie.

Right now, you can experience this combination of spatial recognition and AI using your phone or, generally in less consumer-facing settings, a Hololens or Magic Leap headset.

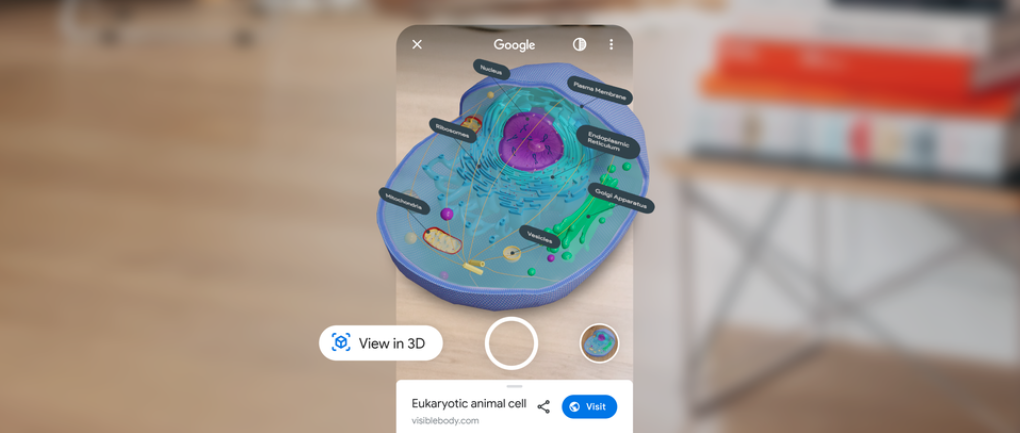

WebXR lets us access 3D content from the browser, overlaying it on the physical world.

Google, for example, recently introduced AR content in search.

Your search results can have an option for “view in 3D”. Click the button and your Chrome browser will pop open a live camera view in which it will place a 3D object such as a cell:

Over time, the number of devices you can use to view these digital overlays and AR content will expand to include consumer-friendly glasses, heads-up displays in cars and other screens.

The AR Cloud Will Supercharge The Mirror World

The AR Cloud will extend these capabilities by “pre-mapping” physical space.

One of the challenges with seeing augmented content is placing it properly. You often have to point your camera for a long time so that your phone can take a decent scan.

While the scanners themselves are improving (Apple added LiDAR to its latest iPad, for example), this will still have limits: you can’t scan very far, and unless you walk around your camera might know there’s a couch in front of you (or a grocery shelf) but not what’s behind it.

But if the environment is “pre-scanned”, someone else will have done all that work for you. It will have mapped out the route from the soup aisle to the bread. And you’ll now be able to quickly tap into an augmented overlay showing you exactly how to get there, with a recipe floating precisely in alignment with the shelves.

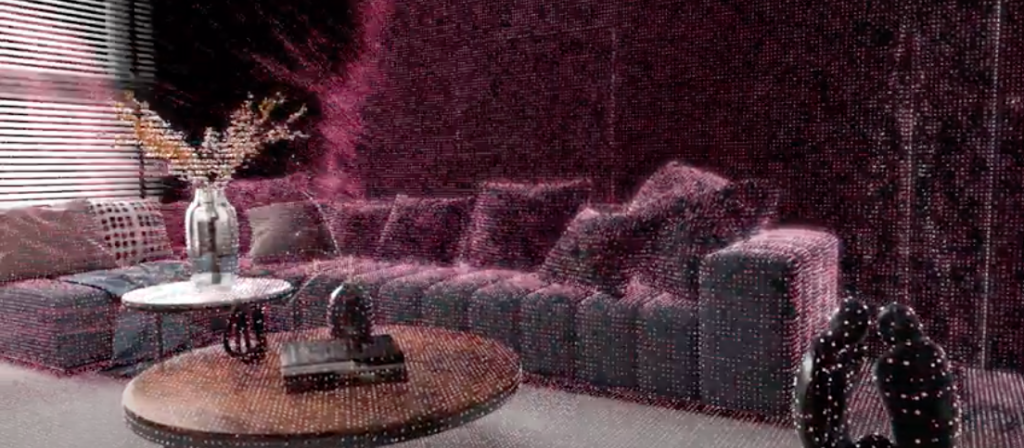

Matterport, although it uses a different approach than, say, Azure Spatial Anchors, is one way to visualize a shared spatial scan.

World-Scale Spatial Mapping

This idea of creating a digital twin of the physical world isn’t confined to indoor spaces.

Companies like Sturfee and Scape allow the creation of city-scale AR Clouds.

And, of course, extending Google Maps to act as an AR Cloud was a foregone conclusion.

The Rights of Physical Objects

OK, it sounds weird. But do physical objects have ‘rights’?

I’ve written about how physical ‘real estate’ might become a larger issue as the AR Cloud builds out.

Developers are already careful about the difference between public and private spaces. Pokemon Go, for example, tries to make sure that a group of players doesn’t invade your backyard. (Niantic, the creators of Pokemon Go, recently acquired 6D.ai, which was already helping to create the AR Cloud.)

But what about the physical objects in those spaces?

Who “Owns” A Crosswalk Sign?

To make this more concrete, imagine a crosswalk sign. You’re wearing AR glasses. Those glasses have enough resolution and capacity for occlusion that they can realistically place 3D objects in a physical space. Objects appear real (and may approach what some researchers call superrealism) and can hide behind or stand in front of real objects.

Now imagine you’re playing a version of Fortnite that has been adapted to AR. You want to build a ramp or construct a fort at the intersection. You’re harvesting materials – bashing down ‘buildings’ for their wood and metal.

Should you have the right to bash down the stop sign?

There’s clearly an issue here of user safety. How will that safety be managed?

The Open AR Cloud Association imagines a semantic mapping of objects so that your device can understand their relationship in a space. In that vision, the space you’ve entered will be spatially mapped and the objects within it will be ‘tagged’: road, building, street light, pedestrian, crosswalk and car.

But who decides whether Fortnite should allow users to bash down the crosswalk sign for metal? Epic Games? The city? A room full of lawyers worried about liability issues?

Who Owns A Billboard?

I can run a Facebook ad using my competitor’s name as a keyword. There have been lawsuits. Because don’t I own my own brand name? Isn’t someone else using my brand for publicity infringing on my rights?

So what about a billboard? And what about a billboard for Adidas?

Will Nike have the right to overlay, in an augmented reality device, their own ad on top? Will they have a right to add ‘counter-programming’ to their competitors ads by placing a competing digital ad that floats next to the physical ad?

Adidas might have rights to their brand and to the publicity associated with that brand. But does the billboard owner have the right for their physical signage not to be defaced?

A Creative Commons For Physical Objects

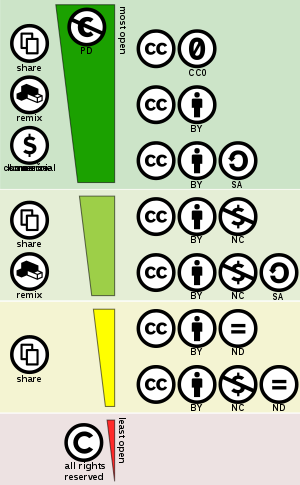

One possible solution to these issues is to have the equivalent of a Creative Commons for physical objects.

A Creative Commons license attaches rights to digital content. For example, it can indicate whether the creator will allow others to freely share their photos or designs.

A Creative Commons license for Augmented Reality (I’ll call it CC-AR for short) could take a similar approach, but focus less on the sharing and commercial side (no one can resell a Stop sign) and more on how those physical objects are used in a AR.

As a preliminary concept, this CC-AR could, for example:

- Define obstruction rights, which would be defined as the right to cover an object in augmented reality

- Do not obstruct (safety) would define that an object should not be obstructed for safety reasons

- Do not obstruct (commercial) would define that the object owner is claiming commercial rights for the object to remain in view

- Obstruct for payment would define that the owner is claiming the right to be compensated for obstruction

- Obstruct (all rights) would define that an object can freely be obstructed

- Define “mash-up” rights, which would define whether an object can be morphed, changed, or otherwise altered in an augmented view. Similar to adaptation rights in a Creative Commons license

- Define attribution rights, which would define whether the owner is claiming rights to how information is ‘attached’ to their object. For example, a city might claim “no attribution” to a street sign, allowing developers to attach overlays such as map or location information. But a brand might claim attribution rights to their bag of chips or can of Coke

Incentives of an AR Creative Commons

There are built-in incentives for a system like this, perhaps even moreso than the traditional Creative Commons.

AR developers, platforms, device-makers and others from industry would benefit from:

- Shared repositories of physical object scans, tags, and rights

- Protection against the legal implications of not properly knowing whether an object represents a safety issue. For example, if they could tap into repositories of city traffic and other signage, the city is taking responsibility for prioritizing safety issues rather than app developers

- Potential access to shared AR Cloud maps provided by private and public entities. A city could provide a spatial map of public properties in order to preserve its rights in public spaces and to provide safety to its citizens. The users of those spatial maps would get access to ‘out of the box’ digital twins in exchange for respecting the CC-AR

The owners of physical objects (cities, companies and other entities) would benefit from their rights, the need for safety, and the user experience of their spaces being respected.

Moving Forward With Designs for the AR Cloud

A lot of the focus in developing the technologies that support the AR Cloud are focused on creating standards for spatial mapping and positioning within these spaces. These standards are important because they will allow users to transition between different spaces, apps and devices.

They also rightly put a lot of emphasis on privacy (to varying degrees) and with some increasing attention to the ethics of VR and AR.

But these discussions have, to a large degree, focused on the digital side of the AR equation, while remaining silent on implications for property ownership and the potential clash between digital overlays and the physical objects they use as reference.

The CC-AR provides a conceptual model for what other kinds of discussions and issues will arise as we build out a mirror world, one in which the physical world is a new operating system and interface.